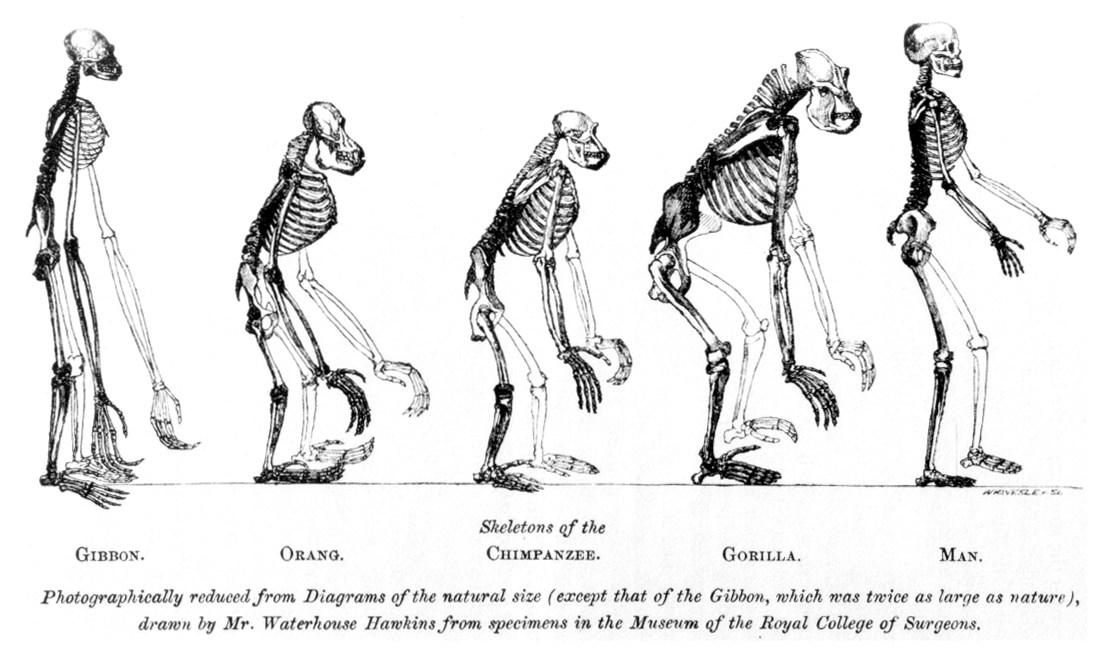

Humans are unique among the great apes in having a tight birth canal and a relatively high risk of feto-pelvic disproportion, when the baby is too big to progress though the canal. Our childbirth difficulties have long been explained as a compromise between efficient bipedal locomotion (favouring a narrow canal) and safe delivery of a large-headed baby (favouring a large canal). However, recent studies have shown that more complex trade-offs are in place. This is what I am investigating with a several collaborators, including Nicole Torres-Tamayo (UCL, University of Zurich), Todd Rae (University of Surrey), and Eishi Hirasaki (Kyoto University); the research has been funded by the Leverhulme Trust, the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation and the EU Synthesys scheme.

Are humans really that unique?

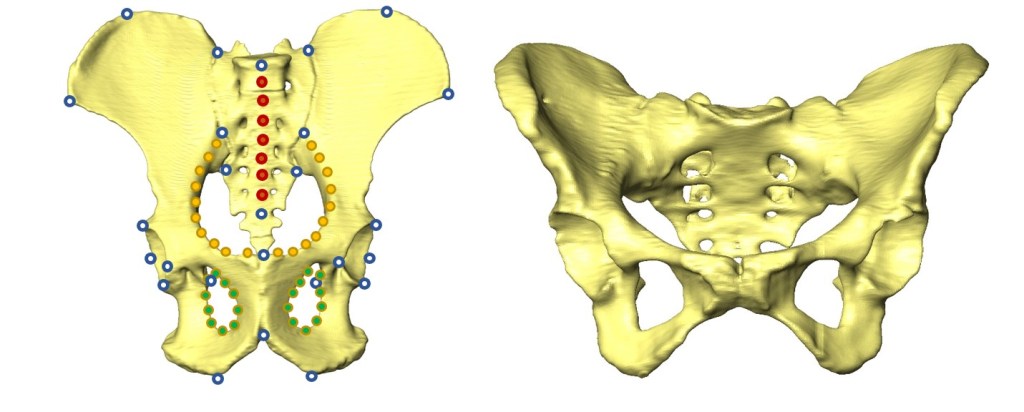

The human birth canal is about the same size, if not a bit smaller, than the baby’s head, leading to a difficult and dangerous birth in our species. Other great apes, on the other hand, have a spacious birth canal in respect to their babies’ size. As we are the only bipedal ape, the obvious conclusion has been that our pelvis changed in response to our adaptation to bipedalism, leading to a tight fit with the baby’s head, further exacerbated by our large brain. If you expand your view to other primates, however, it appears that we are not that unique: gibbons, macaques, squirrel monkeys and other species have a similar tight fit during childbirth. We are have developed new 3D measurements of the birth canal that allow direct comparison across primate species, to investigate in what ways we are unique and in what ways we are not. Some early results are in this preprint.

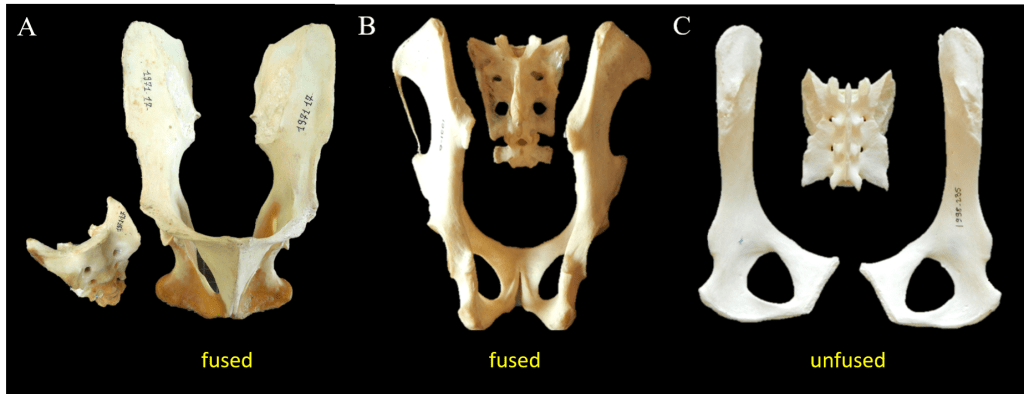

As part of this project, we have looked at the fusion of the pelvic bones in humans and other primates, to see how common the human unfused pubic symphysis is across primate species. This is the joint that connects the two sides of the pelvis at the front, and an unfused joint in humans has been interpreted as an adaptation to maintain a flexible pelvic girdle to give birth to our large babies. We found that fusion occurs in adulthood in most primate species, and but that it tends to happen later (or not at all) in females in respect to males, suggesting that this is likely to be, indeed, an obstetric adaptation in many primates. Humans are not the only species that shows no fusion at all in either sex. You can find the paper here.

Locomotion, posture and obstetrics

Primates are a particularly diverse group of mammals, with very large differences in locomotion, diet and body size. As part of the same wide-ranging project, we are investigating how variation in locomotion, habitual posture, adult and baby size and sexual dimorphism have affected the shape and size of the birth canal across primates. By taking a wide comparative approach, we are testing alternative hypotheses for why humans (and some other primate species) have evolved a tight birth canal.